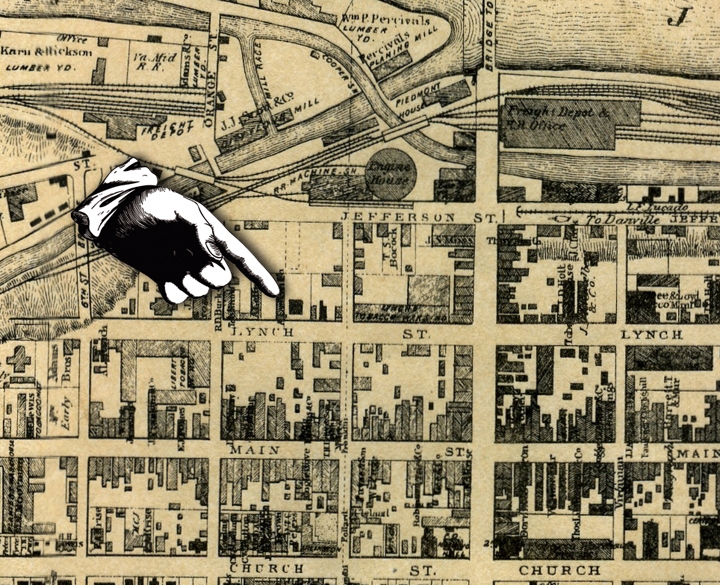

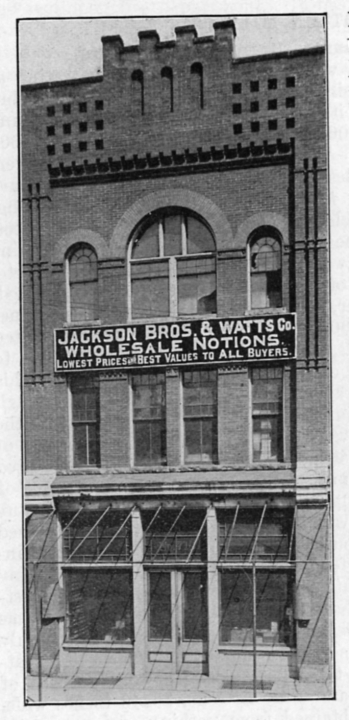

During the 1800s, the red-light district of Lynchburg was commonly referred to as the Buzzards Roost. Houses with madams were located on Commerce Street (then Lynch Street; Lynch Street became Commerce Street in 1894), Jefferson Street, and 7th, 8th, and 10th Streets. In a nod to our city’s history, we decided to name our store after the historic neighborhood. The building dates to the 1890s and originally housed a wholesale grocery store called Gibbs, Hancock, & Tinkle. Subsequent occupants of the building include Jackson Bros. & Watts Co. (1899; notions; photo at left), United States Automatic Loom Attachment Co. (1910), and Fields, Watkins, Co., Inc. (1920; wholesale hats).

Prior to the construction of the building (as well as neighboring buildings), the 700 block of present-day Commerce Street was mostly residential. The late 1800s saw houses with madams located at 715, 719, 720, 721, 722-724, and 726 Commerce Street. Even before the Civil War, Buzzards Roost gained notoriety for its bordellos, bars, and gambling houses. Buzzards Roost had the reputation as one of the worst slums any police department ever had to contend with and was in the zenith of its notoriety during the canal’s packet boat days.

The Lynchburg Virginian of Novemeber 18, 1859, quoted a correspondent of the

Fredericksburg News as writing,”‘Buzzard Roost,’ aka ‘Red Row,’ was pointed out to me by my ‘guide,’ and a wretched looking place it was.”

John Cabell Early (1848-1909) wrote a sketch entitled “Lynchburg in the Fifties,” in which he remembered:

Buzzard’s Roost on Jefferson Street was thronged with the most rowdy and disreputable class of fallen women and tough men, the latter mostly the crews of freight boats. Several murders took place in that locality, and the police had much trouble in keeping the inhabitants in order. On more than one occasion, even in the broad open daylight, there were so many engaged in a free fight that the police could not cope with them by the usual means, but had to get the hose and firemen and drench the belligerents, who, with their ardor thus cooled, might be seen lying about on the street like a lot of drowned bees.

After the Civil War, during reconstruction, in July of 1867, Yankee Col. George P. Buell issued General Order #61 which read in part:

After the Civil War, during reconstruction, in July of 1867, Yankee Col. George P. Buell issued General Order #61 which read in part:

“For the better preservation of the public peace and for the purpose of preventing any disorderly conduct on the part of enlisted men… All houses of ill-fame in the three disreputable localities known as “Buzzard Roost,” “Tin Shingles,” and “Curl’s Row,” will be vacated by the present occupants, and they are hereby ordered to leave the premises within ten days. If found still occupying the premises. Officers will at once remove them, lock up the houses and hold the keys subject to the call of the owner of the property… keys will not be delivered except upon satisfactory assurances of owner that the premises shall be painted or whitewashed and not rented or used except for lawful or reputable purposes.”

Lynchburg’s first red-light district by the river continued to flourish until the early 1900s. As the area became more commercial, the ladies moved to the area near the City Cemetery where a number of the madams, inmates and their families are buried.

Source: Nancy Jamerson Weiland

(While we embrace the history of our city and this area, we are in no way condoning or promoting prostitution or any of the language or content that follows!)

Learn more about the history of the Buzzards Roost by reading the following articles:

Interesting facts about “Buzzards Roost”

The Daily Dispatch: July 23, 1861.

Desperate affray in Lynchburg.

–A correspondent of the Petersburg Express gives the following account of an affray at a locality called Buzzard Roost, in Lynchburg, on Saturday last:

“A fight occurred between two Irishmen named John Spillman and Robert Searson, which resulted in Spillman’s ripping open the abdomen of his adversary with a bowie-knife, from the effects of which Searson died almost instantly. As soon as Spillman committed the deed, he ran into his house, when he was pursued by Col. Leftwich, accompanied by one of his negroes, whom he called to assist him in arresting Spillman. While in the domicile, Messrs. John Pick and David Lawson ran in to see what was the matter. When they entered they met Col. L.’s negro, who they supposed was the person who had killed Searson. In attempting to arrest him, the negro (being a large, athletic man) knocked them both down. As Mr. Pick attempted to arise, he seized the negro. At that moment, Col. L. came out of the room with the knife in his hand that he had taken from Spillman, and supposing that Pick was a comrade of Spillman’s about to kill the negro, he made at him with the knife, inflicting a serious wound upon the back of the hand.–The wound is not thought to be dangerous.–Spillman also had his head badly cut, and is thought to be dangerously hurt, the instrument with which the wound was inflicted having gone through the periosteum; but the skull is supposed by the examining physician not to be fractured. Spillman and the negro were taken before the Mayor, who continued the case until next week.”

“A fight occurred between two Irishmen named John Spillman and Robert Searson, which resulted in Spillman’s ripping open the abdomen of his adversary with a bowie-knife, from the effects of which Searson died almost instantly. As soon as Spillman committed the deed, he ran into his house, when he was pursued by Col. Leftwich, accompanied by one of his negroes, whom he called to assist him in arresting Spillman. While in the domicile, Messrs. John Pick and David Lawson ran in to see what was the matter. When they entered they met Col. L.’s negro, who they supposed was the person who had killed Searson. In attempting to arrest him, the negro (being a large, athletic man) knocked them both down. As Mr. Pick attempted to arise, he seized the negro. At that moment, Col. L. came out of the room with the knife in his hand that he had taken from Spillman, and supposing that Pick was a comrade of Spillman’s about to kill the negro, he made at him with the knife, inflicting a serious wound upon the back of the hand.–The wound is not thought to be dangerous.–Spillman also had his head badly cut, and is thought to be dangerously hurt, the instrument with which the wound was inflicted having gone through the periosteum; but the skull is supposed by the examining physician not to be fractured. Spillman and the negro were taken before the Mayor, who continued the case until next week.”

Lizzie Langley (1833–1891)

Proprietor of one of Lynchburg’s most successful “sporting houses,” located on Lynch Street now know as Commerce Street in the neighborhood known as “Buzzard Roost”